My cousin in Jerusalem, two years older than I, was the last surviving repository of missing pieces in our family history. When I told my daughter he was willing to meet with her, she didn’t hesitate a moment. That’s how we came to be in Israel—and to catch a glimpse of what it’s like to be an Israeli or a Palestinian in that country.

Historical Background: What If . . .

In July 1945 the leaders of the victorious Allies had met in the Minoux villa at Wannsee, on the outskirts of Berlin, to discuss the postwar administration of Germany. Winston Churchill, just days before ceding his place to the anti-Zionist Clement Attlee, shrewdly suggested that part of Germany be split off and designated a Jewish state. His plan had the dual virtue of ensuring autonomy to the world’s surviving Jews and making Germany, architect of their near-annihilation, provide the land. The Germans, of course, had no option to resist; some, indeed, might have agreed that justice was being done. Josef Stalin, happy to grant exit visas to Soviet Jews, embraced Churchill’s plan; Harry Truman followed. With little debate, the group chose the state of Bavaria, rich in symbolism as the birthplace of Nazism and holding within its boundaries Nürnberg, the site of Nazi rallies, Dachau, the first concentration camp, and Berchtesgaden, a favorite hangout of Hitler’s. The choice of Wannsee was likewise deliberate, for it was there, only three years earlier, that the “final solution” to the “Jewish question” had been hatched.

An exodus of Bavarians into neighboring states was expected, although the Jews might show compassion or what German civilians, too, had gone through during the war. Besides, thousands of Germans remembered, after their defeat, that they had been anti-Nazi from the beginning. And as long as they were disarmed, the Germans could not make war on the Jewish state. Should they try in the future, Czechoslovakia and Austria would be bound by treaty to intervene. Eventually a lasting peace would be achieved, and the Jews would treat the Gentiles dwelling among them as welcome guests, in fulfillment of God’s commandment (Leviticus 19:34).

Historical Background: Actually . . .

In July 1945 the leaders of the victorious Allies met in the Cecilienhofat Potsdam, elsewhere on the outskirts of Berlin, to discuss the postwar administration of Germany. Jews weren’t on the agenda. A home for them, less than one-third the size of Bavaria, symbolic in a different way, was proclaimed almost three years later by the United Nations in a former British protectorate inhabited by a majority of unwelcoming Arabs (mostly Muslim but also Christian) and a minority of Jews from prior immigration. No sooner was the Jewish state born than the fighting began. Almost seventy years later, it’s still going on.

Under constant threat from the outset, the new nation nevertheless flourished. In 1967 and again in 1973 Israel turned back invasions by neighboring states. After capturing the West Bank of the Jordan River from Jordan and the Golan Heights from Syria, they were safer against attacks from without. But the victors created new problems by annexing East Jerusalem and establishing more than two hundred Jewish settlements in occupied territory. In the end Israel came to be seen as aggressor.

Our Tour

The following describes my observations, refreshed by notes that Lisa kept along the way. The story would not be worth telling without historical and political context, but my treatment of those subjects is limited by my lack of expertise. Although Jewish, we went with open minds, and any appearance of bias is unintended. Lisa has reviewed the manuscript for factual accuracy. I am immensely grateful to her for conceiving, planning, and executing the tour and bringing a scholarly perspective to it. Lisa is professor and chair of the history department at the University of Iowa.

Our education began just minutes after we left the Tel Aviv airport. The route to our B & B in Beit Sahour, a town adjacent to Bethlehem, took us through Jerusalem on a superhighway accessible only to Israelis. Palestinians, many of whom work legally in Israel, are confined to other roads. In fact, exclusion of Palestinians is not uncommon on Israel’s major highways. It was the first of many unpleasant revelations.

Our hosts were West Bank Palestinians: Christian, educated, fluent in English, and well-to-do. Their balcony commanded a panoramic view that included the Church of the Nativity in nearby Bethlehem and the Har Homa Jewish settlement. The latter, like all settlements, was surrounded by a patrolled security barrier, which in this case totally isolated a Palestinian farmer from his fields.

Naturally we visited Bethlehem, as tourists do. But its outskirts were just as interesting as the better-known historic sites. First was Aida (no relation to the opera), a Palestinian refugee camp in occupied Palestinian territory. What makes it special is its program to educate its children in the arts and theater, under the guiding principle that “Beautiful Resistance” is preferable to violence. The number 194, the U.N. General Assembly resolution addressing the right of return, is prominently displayed, and the entrance gate is a huge keyhole-shaped arch with a key on its top bearing the words “Not for Sale.”

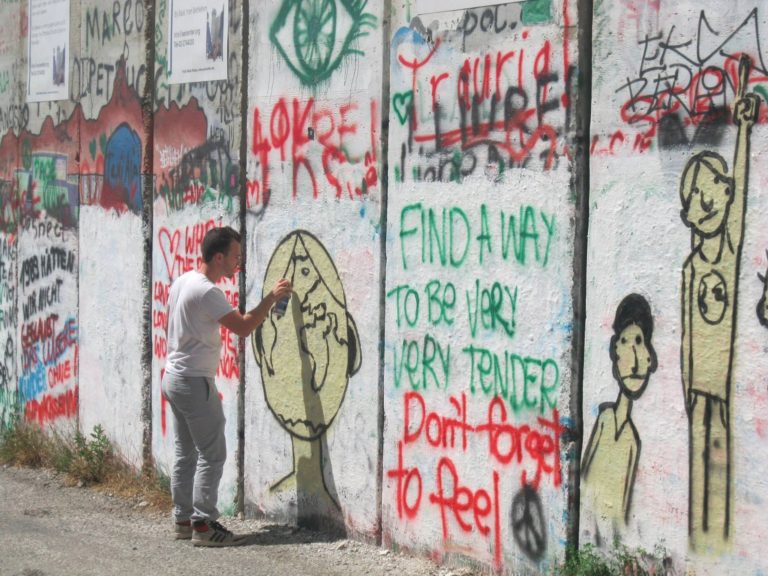

Second was the Wall, which we saw up close for the first time. It was covered with graffiti, some of it text (in English and other languages), much of it graphic, mostly expressing messages of peace. Visitors make space for their art by spraying white paint over the previous artist’s work, as Lisa’s son Josh, who accompanied us, did.

Across the street from the wall was a souvenir shop, offering the usual tourist kitsch, albeit with a Palestinian bent. A refrigerator magnet showing a Palestinian girl frisking a disarmed Israeli soldier caught my eye.

Our hosts treated us warmly. The husband introduced me to arak (anise-flavored, resembling ouzo), his favorite liqueur, and as we drank together I asked him how he felt about U.S. policy toward the Palestinians. His reply: “President Obama may mean well, but he can’t do anything without permission from Congress, and they’re all Jews.” I pointed out that the majority of congressmen and women are Christian like himself, but he brushed me off. Facts were not about to get between this schoolteacher and what he needed to believe.

A public bus took us from Bethlehem to Jerusalem, where we visited the Yad Vashem museum before proceeding to my cousin’s apartment. The bus fare was modest, appropriate to commuter traffic. We found ourselves in the company of Palestinian workers en route to their jobs and had our first experience with a checkpoint. Just outside the Wall two Israeli police, armed with submachine guns, boarded the bus. They herded the Palestinians off, to be screened for legitimacy. We showed our passports and were allowed to stay in our seats. The bus then proceeded through the barrier and the Palestinian passengers came back on board. We soon discovered that this routine, submachine guns and all, was the norm at checkpoints, applied to taxis and private vehicles as well as buses.

After a day’s sightseeing in Jerusalem’s Old City, we visited Tekoa, an established Jewish settlement in the West Bank. We were met by an American-born settler — journalist, Middle East security analyst, and director of the Islam-Israel Fellowship — who spoke with us about living in peace with the Arabs (settlers don’t call them Palestinians). To illustrate his point, he told of his cordial relationship with he Arab contractor he hired for a building project; the construction crew likewise was Arab. (Regrettably we did not ask whether there were also Arabs employing Jews.) Picking us up later, he distributed a piece he had written, “ReIslamification,” in which he quoted the Muslim scholar Sheikh Abdul Palazzias saying that “the good Moslem [sic] should be a Zionist . . . [and] a Moslem who is not a Zionist, is not a Moslem” — Zionism meaning “reestablishment of the Children of Israel in their homeland.” Palazzi, it turns out, is a controversial character with variable allegiance to Islam and/or Hinduism and dubious credibility as an advocate for Zionism.

The term “settlement” can be deceptive. Tekoa is an actively growing community of about 3,000 with paved streets, homes, public areas, shops, etc. On a wall in the building in which our hosts met us was a series of maps showing the continuing expansion of Tekoa since its founding in the 1970s. This, of course, is the intent of the settlements: to grow into permanent, self-sustaining communities and perpetuate Israeli presence in captured land. Palestinians, among others worldwide, point out that the settlements violate the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949), which forbids transfer of civilian populations into occupied territory. Our settler hosts consider that argument irrelevant, holding that the West Bank (known to them as Judea and Samaria) was promised to the Jews by the League of Nations in 1922 and illegally annexed by Jordan after the State of Israel had been established. In other words, it’s not occupied territory; it’s reclaimed territory.

We were received by two well-educated, articulate spokesmen, both American-born, as are 15% of all West Bank settlers. One a former social worker and Viet Nam War conscientious objector, felt completely comfortable in the present. “I live right here in Tekoa, in Israel. The so-called West Bank, it’s Israel, it’s all our land.” Asked about the Oslo Accords, they “didn’t exist, because the Arabs never signed them” (an assertion neither Lisa nor I have been able to confirm). The other was a legal scholar who had practiced law in the U.S. I asked him what he thought about U.S. policy toward Israel. “Atrocious from the very beginning,” was his answer. The U.S., like the British before them, had consistently frustrated the Jews and favored the Arabs. At that point I realized that Israelis and Palestinians actually found common ground on one point: The U.S. favors the other side.

The director of the Islam-Israel Fellowship would have shared her wish for peaceful coexistence, but without abolishing Israel (while, by relentless expansion of settlements, all but choking Palestine to death). His formula for peace would boil down to this: Israeli land-owners should treat their Palestinian subjects like friends (Leviticus 19:34).

After a brief walking tour of the ancient city of Acre (Akko), we drove to the modern city of Tel Aviv where, as in Haifa, residents and tourists alike seemed to be living a normal life. Both cities are at a safe distance from disputed territory.

We flew home two days later.

Establishment of the State of Israel, the ultimate goal of decades of Zionism, in 1948 was precipitated by the recent German genocide against Jews. Arabs indigenous to the designated land, who had had no hand in those atrocities, were displaced and dispossessed to make room for the new state. The resulting clash began a circle of violence that continues to this day.

Could those consequences have been forseen in 1948?

What if the imagined conference at Wannsee — call it Wannsee II for context — had actually taken place in 1945? Would Israel (formerly Bavaria) and the rest of Germany be coexisting peacefully today?

My cousin died five months after our visit.