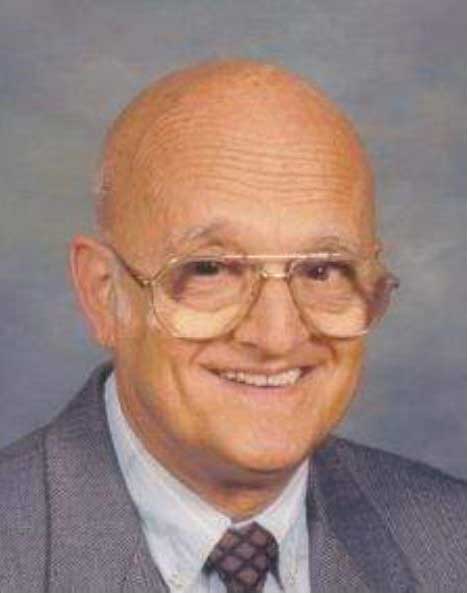

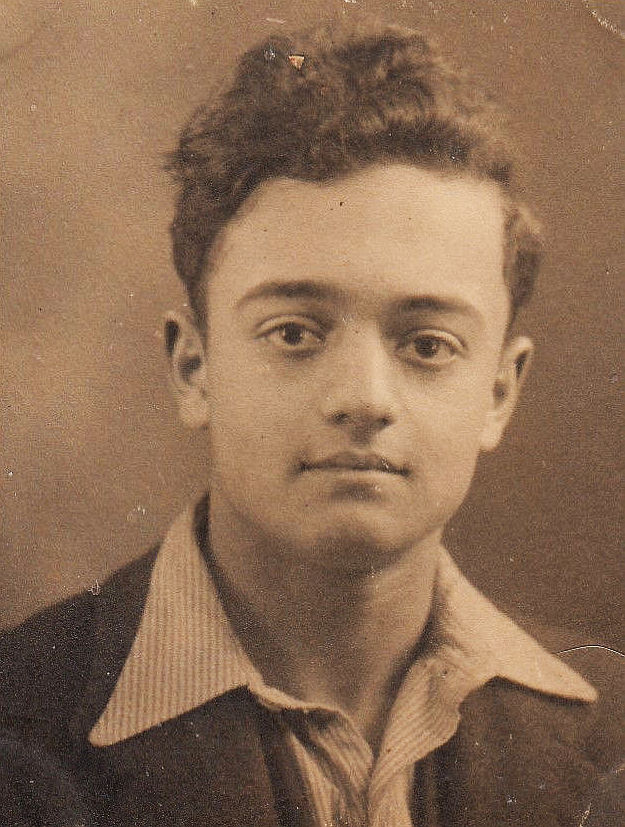

HERB – Herbert Simon Heineman (née Heinemann)

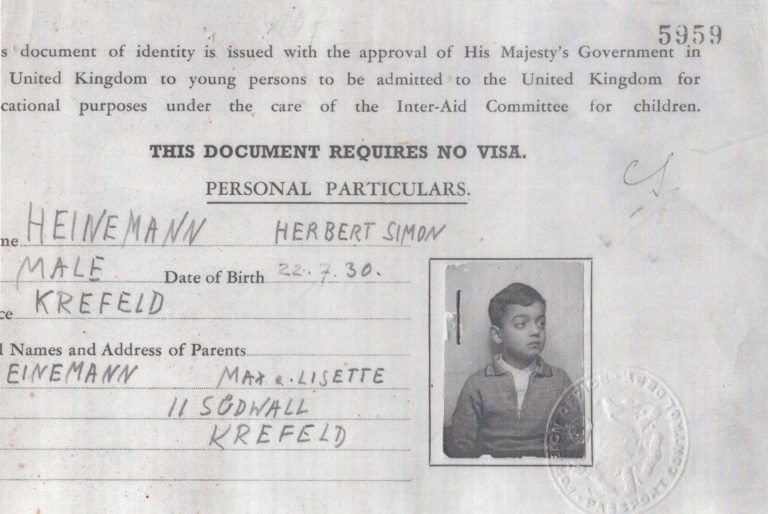

I was born in Krefeld, Germany, July 22, 1930, and sent to England in 1939 with the Kindertransport program. In 1948 I immigrated to the United States, graduated from City College of New York in 1953 and New York University Medical School in 1957. I interned and began my residency at Duke Hospital, then went to Presbyterian Hospital, Pittsburgh, for additional years of residency and fellowship. I was living in Pittsburgh when I married Maggie Andrus. Our children Lisa, Jim, and Sue were born there. The family moved to Philadelphia in 1968. An internist with a specialty in infectious diseases, the final years of my career were as Laboratory Director for the Philadelphia Health Department. Maggie and I moved to Lumberton, NJ, in 2001. After retiring I engaged in several volunteer activities and I wrote memoirs, short stories, poetry, and the novel Eden’s Garden. In 2012 and 2013 Lisa and I visited the places of my childhood in both England and Germany. My accounts of those trips are included in the pilgrimages section of this website.

Acknowledgement: For the following narrative, my wife Maggie has pulled together words and pictures from various sources, mostly from my daughter Lisa’s notes of her recorded interviews with me in which I endeavored to recall events that had occurred many years earlier. I also want to credit Maggie for collecting my writings for this website and I thank Ann Campbell for the design and implementation of the site.

CHILDHOOD IN GERMANY 1930-1939

I remember three addresses where I lived in Krefeld, each with particular associations. In order:

- Breitestr 66 (no longer to be found — maybe bombed). Once we all had the grippe (flu), but my mother forced herself out of bed to take care of the rest of us. She was a fond mother to us children. One morning there was a huge roar. I looked out the window at the sky and saw the Graf Zeppelin. It was scary.

- Malmedystr 55 (subsequently renamed Lewerentzstr 55). It was still standing when Lisa and I visited in 2013. The toilet made a frightening sound when flushing. We had an enclosed backyard with beautiful ladybugs (black with many yellow dots). I was able to climb over the wall into the backyard of my friend Egon Steinhardt, who lived around the corner on Ölschlägerstr. Egon was not sent to England; he was probably killed in concentration camp. Malmedystr is where the S.A. (Storm Troopers) came on the night of Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938, trashing our apartment, destroying furniture, ceramics, and glassware, and turning the gas on without lighting the burner. My mother discovered that in time to avoid disaster.

- Südwall 11 (no longer to be found — maybe bombed or torn down for redevelopment). It was a smaller place than Malmedystr but I don’t think we were crowded. There was an enclosed backyard in which my father and I used to kick a soccer ball around. My father was a soccer fan and occasionally accompanied the local team by bus to other places they played. I think I went with him once. Naturally, we went to local games. While my father and I watched the soccer, Eric ran around the grandstand pretending he was a streetcar.

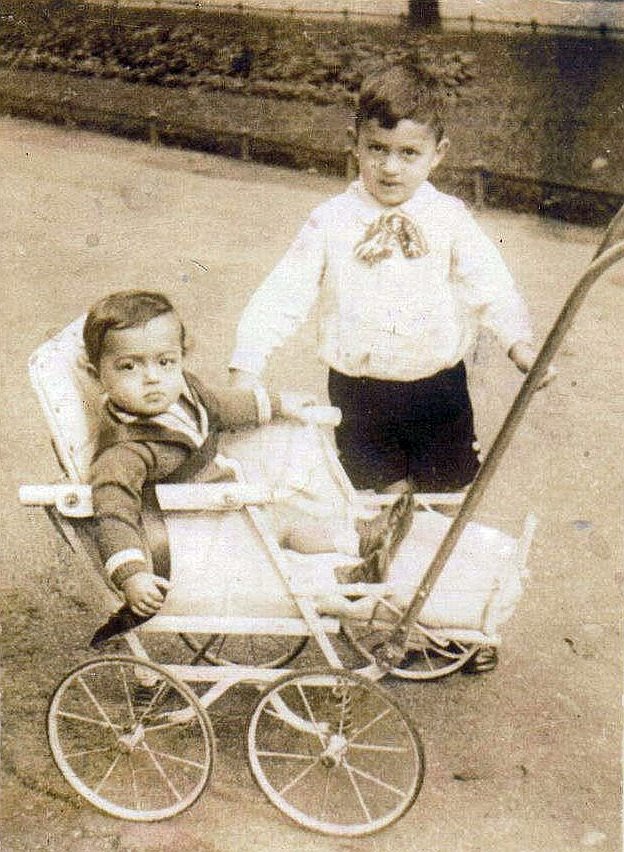

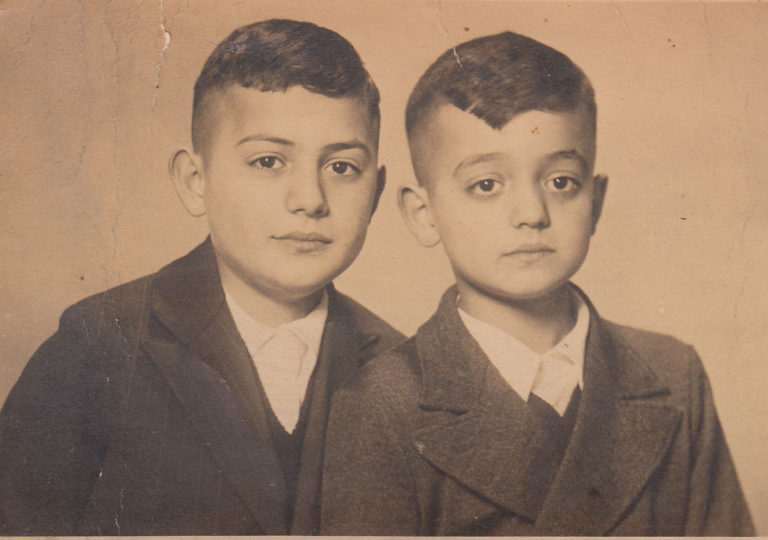

My brother Eric liked playing with batteries, bulbs, electric bells, etc. He had a lifelong fascination with electric stuff. He had no interest in sports and read only newspapers and trade journals. He wanted me to acknowledge that he was the Older Brother (true, by 3 years and 7 weeks). He was the better son, always obedient and attentive to his parents; I was abrasive and fresh, and sassed everybody including my parents. My Uncle Max said of me: Das Ei will klüger als das Huhn sein (the egg wants to be smarter than the chicken).

Eric was my only sibling. He was born in 1927 and I in 1930. In between, born in 1928, was a girl named Liselotte (Lilo), who died within a few days of birth. I suspect the cause was Rh incompatibility. I survived the subsequent pregnancy because I’m Rh-negative. It’s possible that I owe my existence to Lilo’s death if my parents only intended to have two children. However, such a conversation with my mother never took place.

The day after our Malmedystr home was trashed my father was arrested. We were afraid he was going to be sent to Dachau, but he was released, maybe because he was a wounded WWI veteran, but that’s speculative. That evening we went to Cologne (about 35 miles south of Krefeld). Uncle Max, my mother’s middle brother, lived there, but there were other relatives too. I don’t remember with whom we stayed or how long. I don’t think we ever returned to Malmedystr to live, because I left for England 7 months later and that included our residence on Südwall.

For a kid not even nine years old when I left Germany, I had done quite a bit of traveling by train on my own, although I was taken to the station and picked up. By train I visited my grandmother (Oma), my mother’s youngest brother Uncle Eric (Onkel Erich), his wife Aunt Kate (Tante Käthe), and his daughter Cousin Inge in Irlich (now incorporated into Neuwied). Inge is 3 weeks my junior. I routinely made her cry; she was such a baby. lamb. Other trips were to Nordenstadt, near Wiesbaden, visiting my mother’s oldest brother Uncle Alfred, Aunt Tillie, and Cousin Hilde, and to some summer camp or other on the North Sea. I don’t remember my ages at any of these trips. Eric did not accompany me on them.

Like most Jews I’ve known, we had our own definition of kosher. We did not eat pork. We also observed the separation of meat and dairy foods, to the extent that if our mother served a dairy dessert right after a meat meal, she told us not to tell anyone. Until it was burned down we went to synagogue in Krefeld more or less regularly, not just on the High Holy Days. In my later childhood and adulthood I tended to compare Jewish worship services to those memories, not architecturally so much as spiritually and emotionally. Thus I felt comfortable in synagogues as well as in homes improvised for that purpose when the services were traditional, i.e. in Hebrew and following a prescribed order. The “new-age” experience of the chavurah in Philadelphia turned me off completely.

Both Eric and I attended a two-room Jewish school on St.-Anton-Straße, Krefeld. My childhood friends were Kläre Kahn, Egon Steinhardt, Walter Bach, and Lutz (Ludwig) David. Egon and Walter and Kläre did not survive the war, but Lutz ended up in the U.S.

Knowing now what happened to those other kids (and thousands like them), I realize that my parents showed extraordinary foresight and courage in sending us abroad.

We took English lessons from a family friend, Erich Jakobs, when our parents had made plans for our emigration. I don’t remember talking with Eric about our impending emigration; my parents, of course, talked about it a lot, and arranged for our English lessons. I don’t think I was scared, maybe because I had traveled away from home on other occasions.

I remember being taken shopping for a suitcase and a watch. We left for England in June 1939. The watch stopped running when I got to England. I wrote to my parents, suggesting that the rocking motion of the ship was responsible (…vielleicht weil das Schiff gewackelt hat). They thought that was cute.

GROWING UP IN ENGLAND 1939-1948

Krefeld refugees went by train to Hoek van Holland (I on June 6, Eric on June 20), accompanied by an escort who later returned to escort another group. My cabin on the ship had bunk beds; I slept below and a new friend, Karl Ludwig Selig, slept on top. (Decades later Karl [now Charlie] had a successful insurance business in Great Neck, L.I.)

The ship sailed overnight to Harwich, where I recall a vending machine selling chocolate. Sometime later — don’t know how long, days or weeks — I arrived in Margate. The interval is erased from my mind except waking up the first morning terribly homesick. Later I found out from Charlie that we had been quarantined because someone had scarlet fever.

My brother Eric caught up with me in Margate. I don’t remember his saying anything about the interval between our departures when he was alone with our parents.

In Margate, we lived in a hostel named Rowden Hall, 13 Third Avenue, Cliftonville (a suburb of Margate). I remember lots of kids, probably all boys. There was an outbreak of mumps. Along with other kids I was quarantined. We were told to chew gum to make saliva flow. When done chewing we’d threw the gum against the wall, where it stuck. A pleasant quarantine.

The matron was pretty sadistic. Once I wrote a letter to my parents and drew flowers in the margins (probably for one of my parents’ birthday). The censor bounced it because they suspected a coded message. The matron showed the letter to the other kids so everyone could have a good laugh at my expense.

We played a lot of soccer. One guy (Hermann Schulewitz), fearless and reckless, broke his leg. Next day he was back on the soccer field with his leg in a cast. The kids spoke mostly German among themselves, as well as broken English, e.g. “What do you wish?” “I wisch the table — or the floor.” (Wischen is German for wipe). We probably had English classes in prep for school, but I don’t remember them. Strangely, I do remember Spanish lessons. I suspect someone knew Spanish and wanted to be useful.

When Eric and I arrived we spoke only the little English we had learned from the private tutor in Krefeld. In September 1939 I started school (co-ed) in Margate. How I’d mastered enough English by then to go to that school I can’t imagine, but I survived. One of the teachers was Miss Hillyard. The English children were kind to me. I felt like a pet. One girl gave me chocolate. Somewhere in town there was a fair, where we tried to win prizes. I learned the word “Push” from a swinging flap behind which you could pick up anything you’d won.

The hostel was a short walk from the beach. One day, looking across the English Channel, we saw a ship sinking. It had probably run onto a mine. On another day, going home from school, I heard or read an announcement that Norway had been invaded.

I followed the war closely, like watching or reading a thriller. The North African campaign, the Russian campaign, the naval battles (Hood, Bismarck, Prince of Wales, Repulse, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Prinz Eugen), Pearl Harbor, Bataan, etc. etc. Rommel and Montgomery were both heroic figures, though I had no doubt whose side I was on.

Early in the war gas masks were distributed in cardboard containers to hang around our necks for emergency use (based on the use of gas in WWI). Luckily we never had to use them.

Mailboxes were covered with a paint that would change color if exposed to whatever poisonous gas they expected might come. We were instructed to keep our eyes on them.

I don’t remember if there were practice air raids.

I don’t remember specifically knowing about Dunkirk, though in retrospect it would have been impossible to miss, especially following the news as I was.

Evacuation to the Midlands

On an uncomfortably hot day in June 1940 all children from the Southeast, including British, were evacuated to the Midlands. We walked to the train station, carrying our suitcases, and waited for hours. I don’t remember the train ride. That afternoon/evening we were deposited in the village of Chase Terrace. We were billeted with an elderly couple, who had obviously been recruited because they didn’t seem capable of handling a pair of German refugee kids. I don’t remember their names, but I do remember they had a pig.

English families throughout the area were pressured, if not forced, to take kids in, and were given a small stipend for expenses. The exact amount, I believe, was 10s 6d per week per child. The English currency at that time was a dreadful tangle of pounds, shillings, and pence [d stands for denarius, an old coin of small denomination], not to mention farthings, crowns and guineas. All prices and, worse, calculations had to be done in 3 columns, ₤-s-d, and none were multiples of 10 of any other.

After a few days we were transferred to a younger couple with kids our age — twin boys. We got into fights. One of us called the boys pigs. They ran crying to their parents, and we were thrown out.

Our next foster parents, George and Florence Turner, lived in the adjacent village of Boney Hay; theirs was a semidetached house at 55 The Crescent. We stayed with them from 1940 to 1942. They had a 5- or 6-year-old daughter named Iris, whom we would tease by calling her Fanny. She also went off crying, but Mrs. Turner simply reprimanded us and allowed us to stay. Mr. Turner was a taciturn and sullen-appearing guy but seemed harmless enough. He’d go to work in the coal mine early in the morning and come home late in the evening and wouldn’t have a lot to say. He worked a 5½-day week. Saturday afternoon he came home and for the rest of Saturday and all of Sunday most of the time the Turners and their neighbors would sit around the table playing whist. Sometimes they went out to visit friends or relatives (I don’t remember names), and sometimes we went with them. One place we visited was the town of Cannock. Eric and I also went to Cannock on our own to see a movie. From those movies I remember Deanna Durbin and George Formby, a famous comedian. There was also a cinema on Sankey’s Corner in Chase Terrace, where I remember seeing a matinee with Flash Gordon.

The Turner house had no central heat. One fireplace in the living room heated the whole house. Mr. Turner would bank the coal fire at night (a skilled job that only he knew how to do); next morning he’d rake it and throw on more coal, and the fire came back on. This was useful because starting a coal fire from scratch involved newspaper, wood, and coal — and it didn’t always catch.

The war touched us mostly by the blackout requirement, with air-raid wardens knocking on the door if any light showed in the dark. We got used to nightly bombings, generally targeted at nearby cities but close enough for us to hear the bomb blasts. We listened in on the infamous bombing of Coventry — a city of dubious military importance. We also fancied we could tell the German planes from the British by the sound of their engines. (That really was fanciful!) One bomb fell in Chase Terrace and made a big crater.

Sunday dinner was usually mutton with mashed or boiled potatoes and peas and was tasty. I don’t remember soup or dessert. But the leftover mutton would get served cold on Monday, Tuesday, or however long it lasted. I disliked that. I don’t remember breakfasts or suppers, or whether we took lunch to school. Milk was delivered in ½-pint bottles to schools for all students.

Our next-door neighbors on The Crescent, the Thompsons, had a big German shepherd named Tess. George Kronenberg, my brother’s friend, lived down the street. Later he emigrated to the USA and lived in Cleveland, working for American Greetings. We also met him and his wife Sally at the second Kindertransport Reunion in London in 1999. George’s outstanding characteristics were tossing from side to side in his sleep and dressing impeccably. In fact, when in his dress trousers he was reluctant to sit down for fear of ruining the creases.

When we got on Mrs. Turner’s nerves, she’d tell us to go out and play. So we spent a lot of time outdoors. Once I bounced a rock off another and it struck a little kid in the face. That scared me but I wasn’t punished. I remember trying knife throwing against a tree; I got pretty good at making it stick.

We also had some chores, like filling the coal bin. I don’t recall kitchen duties.

The elementary school in those years was in Chase Terrace. Many years later I learned that I used to walk Iris to and from school. That’s where I started reading comic books. The school had other evacuees, including other Rowden Hall kids who lived in both Chase Terrace and Boney Hay. We mixed with the British kids, didn’t self-segregate with German Jewish kids. We didn’t really know who the British evacuees were as opposed to the locals. I played soccer with older kids in the village, who seemed to enjoy my participation. Interestingly, I don’t remember doing anything together with my brother, except the occasional trip to Cannock.

There was no synagogue. I am not aware that any Jews lived in the area. The Turners were not churchgoers, nominally Protestant but not practicing. Our lack of Jewish education came to the attention of agencies in London responsible for Jewish kids (Bloomsbury House). A Mr. Winter was sent out to meet with the Jewish refugee children and collected information that was then used to corral us into a hostel in the village of Aldridge, near Walsall. We moved there in 1942.

Other kids moved to other hostels or families. Some went to Birmingham which had a Jewish community.

Our hostel in Aldrich was run by Rabbi Dr. Max Koehler Dr. phil. His (second) wife was our surrogate mother. He had two daughters, Ruth and Rosel, about 13 and 11, from his first marriage. Rabbi Koehler was probably in his 40s. Ruth eventually emigrated to the USA and died in middle age in Asbury Park, NJ; Rosel went to Israel and was doing well last I heard (from Gilda Moss Haber).

There were enough boys for a minyan. Services were held every Friday evening and Saturday morning. I was one of the youngest kids. Some were already bar mitzvah; mine took place there, but Eric had passed the age and never went through the rite. The place was strictly kosher. No lighting fires, tearing papers, carrying anything, etc on Shabbat. Gentiles living next door turned our lights on and off on Shabbat. There was a nice back yard, in which we played ball.

Some of us (I in particular) sassed Rabbi Koehler and we also suspected he was eating our butter ration. The house, at 2 Walsall Wood Road, was old and decrepit. (It’s no longer standing.) There was a large kitchen on the first floor and several bedrooms on the second. Eric and I shared a room with George Kronenberg and possibly one other boy.

One day George had to have a tooth pulled. Next thing, he was hospitalized for uncontrollable bleeding. He had hemophilia, previously unrecognized. His life seemed to hang in the balance, so Rabbi Koehler performed the ritual of changing George’s Hebrew name in order to confuse the Angel of Death (“sorry, no one here by that name”). George survived.

Eric was sent to a technical school in Aldridge or somewhere nearby. I, along with Walter Hoffmann, commuted by bus to Walsall, attending Queen Mary’s Grammar School, an elite, excellent school with a proud tradition dating to its founding in 1554 by Queen Mary Tudor. Hoffmann and I always competed for #1 and #2 in the class. The grading system was strictly competitive, and each test was followed by the posting of a class list in rank order. Hoffmann and I were the only non-English kids there. The buildings were very old — not exactly 16th century old, although I once thought so. Ours was a boys’ school; girls were in another school on the other side of a wall. Most graduates went on to “read” history, philosophy, medicine, etc. at university.

All the students belonged to a “House.” Mine was Gnosill; our sports shirt (which I still have) had horizontal light and dark blue stripes. I played soccer in the schoolyard during break. Wednesday afternoon was Field Day, when we were all marshaled to the sports field for rugby. I’d never played rugby, but that was the only game. So I got on the field, listened to the rules, and went into action. Shortly a guy named Giles — not big but fast — came thundering down the field. My job was to tackle him; instead, Giles slapped me in the face and kept running. After that I didn’t play rugby but stayed in school Wednesday afternoons with the other sissies.

There were some memorable teachers. One was a former boxer named W. E. Terry (WET). He taught physics and was as mean as they come. He made the kids grade each other’s papers. Once I found that the kid who’d graded mine had short-changed me. WET wasn’t interested. He may have told me to stop whining.

Mr. Parris, affectionately known as Gobbo, taught math (maths in England). He was nice. Gobbo thought I was really good at math, which was true.

The headmaster, H.M. Butler, dignified and gentle, taught geography. The history teacher was a tall woman who looked like Condi Rice (but white). She was the only teacher I knew with a doctoral degree, though there may have been others I didn’t know. I don’t remember her name, but I remember hating history, which seemed to be nothing but rote memorization of dates.

The French teacher drilled us in pronunciation at the beginning of every class period; the class stood and recited the entire list of vowels in unison. He was a nice guy. (I really appreciated the value of that drill for English-speakers when I took an advanced course in French at City College of New York. That teacher’s pronunciation was awful.)

Latin was my best subject, the one Hoffmann never beat me at. The teacher introduced us to Latin literature with Seneca’s “Vita brevis est, ars longa,” with a flicker of a smile.

The geometry teacher looked like George Bernard Shaw (or Freud, or Tchaikowsky). He used concrete techniques in teaching, e.g., he would draw a square on the blackboard and then say something like, “Now we’re going to pick up square abcd, being careful not to drop any chalk along the way, and put it on side ab of this triangle” — and so on till he had proved some theorem or other. Then he’d turn around and without warning throw the board eraser at the kid in the back row who wasn’t paying attention.

During my time there no bombs fell in the schoolyard. (The school website says this happened but did not give the year.)

I still have the school cap, English-type with visor, green, red, and yellow stripes. I wore the cap and similarly colored school tie but never owned the green blazer that went with them.

After one year we had to decide which track to take, humanities or sciences. Hoffmann went for humanities; I went for sciences. So he learned Greek while I learned chemistry. I’m glad I learned chemistry, but sorry I didn’t learn Greek.

Queen Mary’s Grammar School had a chapter of the Air Training Corps for youth. The minimum age was 15, but I was so enthusiastic that I participated in boot drill, Morse code, and aircraft recognition even though I was too young to qualify for a uniform.

I visited Queen Mary’s in 1989, the year of the first ROK (Reunion of Kindertransport). By now the boys were on a new modern campus; the old one, where I had gone, had been handed over to the girls. A senior girl (“sixth-former”) showed us around. In an aside, she boasted that the girls, in the old building, did every bit as well as the boys on the School Certificate examination.

That hostel too broke up. Obviously it was necessary to reorganize us fairly often — or perhaps the building was a fire hazard. Next I went to a hostel on Bury Old Road (I believe) in Salford, a town adjacent to Manchester. I don’t remember the name of this matron or any of her characteristics. I played a lot of chess and ping-pong there. Once I got into an argument with an older kid named Bully (sic), who punched me in the nose and made it bleed. The matron was eventually replaced by a man who played classical piano.

Manchester/Salford was where I discovered my liking for classical music; I don’t know the moment or the place. I also took a few piano lessons from the man who ran the hostel, but conditions were not conducive to developing any skill.

A Mr. Falk, who was genuinely pious, lived in the neighborhood with his wife, who wore a turban. Someone had told Mr. Falk that I was a good student, and he wanted to spend time with me in Jewish learning (Talmud, Mishna, Shulchan Aroch). I went there a few times a week for studies. I was not exactly crazy about this but didn’t feel like resisting either, so I followed along. Mr. Falk was kind. His wife brought cake and tea, which we drank from a glass in a metal frame. He wanted me to go to yeshiva, but the headmaster of my school had other ideas. Mr. Falk thought I should have a more Jewish environment anyway and got me billeted at the house of, I believe, Mr. and Mrs. Halberstadt.

Mr. Halberstadt was religious but he wasn’t all that nice. One day I came home bragging that I’d hit the B button (coin return) on a public phone and lots of coins had come out. Instead of applauding my luck, he chastised me for taking other people’s money.

From 1944 to 1947 I attended North Manchester High School for Boys (NMHSB). I commuted from the hostel in Manchester and then from the hostel in Salford. Somewhere along the line I purchased a 3-speed bike, which allowed me to save my allotted bus fare for luxuries. I passed my School Certificate examination in 1945 and, by the law of that day, could have left school. University-bound students, however, stayed on 2 more years, and in 1947 I got my Higher School Certificate. (The grading system was Pass, Credit, or Distinction. I got eight Distinctions and one Credit — in history.)

I remember the NMHSB headmaster, F.M. Burnett, as an Alistair Sim look-alike, beetle-browed and scary. And he swung a vicious cane. Every day at the beginning of classes, boys commended to his attention were sent to his office to line up, hold out their hands, and get caned across the palms. I paid my dues too. But I was good at math, which was Burnett’s subject and which he taught. In fact, he disapproved of my plans for medicine (med’cin in England) and thought I should read maths. (I sometimes wonder about that fork in my road, but of course I was a Jewish boy, and I thought I had to go into either medicine, law, or accounting.)

We seniors had our most fun in the greenhouse, which stuck out from the walkway in the interior courtyard. There we studied botany, with a teacher who raised no objection to our raising a brown, toxic stink by pouring concentrated nitric acid on mercury to produce nitrogen dioxide. Among my willing classmates were Goldstone, Greenberg, and another whose name I’ve forgotten. Then there was Whittaker, a jazz fiend who was constantly snapping his fingers.

In 1989 I revisited North Manchester High School, which now admitted girls. The position of headmaster had been replaced by that of head teacher, but the school looked just like it had in 1947, including the greenhouse. My name was on a wall plaque in the auditorium, as winner of a scholarship to Salford University. Emigration prevented me from using it.

Meanwhile

Rabbi Koehler had taken charge of the White House hostel in Great Chesterford. The children were mostly girls (Helga Beer, Irene Stein, Gilda Moss, Selma Laufer, Marta Jellinek, et al) ranging from 12 years up, and a sprinkling of much younger boys. Gilda, alone among all those German kids, was a native of London. She now lives in Silver Spring, MD. For the High Holidays Rabbi Koehler wanted to have proper services. To assemble a minyan, which neither boys under 13 nor girls any age could provide, Rabbi Koehler invited boys he knew from Aldridge: Eric, Cousin Gus (Karola’s youngest), best friend Joey, Hermann Schulewitz, Ralph and Alfred Freifeld, and others. It took all day and 5 trains to get from Manchester to Great Chesterford.

Irene (age 12) and I (14) got interested in each other and kept up a twice-weekly correspondence signed with kisses for almost 2 years. I had to steam open the letters arriving on Saturdays because orthodox Jews don’t tear or cut paper on the Sabbath.

The White House is in the background of both photos. Irene is on the left in the 1946 photo, along with Hermann Schulewitz and Helga Beer. In 1989 Irene posed in front of the White House when we visited it following the 50-year reunion of Kindertransport.

Irene came to England on a Kindertransport in May 1939 (age 7). Before moving to the White House she lived with relatives, who exploited her and stole from her. Her parents were divorced. Her mother emigrated to Chile before the war but didn’t take Irene because her father had custody. He fled east, through Poland and the USSR, and ended up in Shanghai. After the war he came to Stockton, CA. Because of his circumstances he agreed that Irene should join her mother in Chile in 1947.

Irene now has Alzheimer’s disease. “Memory, Long Term and Short” is a poem I wrote about her in 2015.

Reunion with Parents

When my parents were notified of their deportation in July 1942, they passed on the information to us. So we knew where they were going. From Terezin (Theresienstadt) they were permitted monthly 25-word messages via the International Red Cross. I don’t remember whether they were handwritten or typed.

Eric constantly pursued information about our parents (via Jewish committees) and made sure that both of us sent messages. After the war he succeeded in tracking them down.

Eric left Manchester for London in late 1944 or early 1945 and found a job in a radio repair shop. He witnessed the rocket attacks toward the end of the war. He was also there to welcome our parents when they came to London in November 1946.

Our parents, after a circuitous path through Deggendorf (a displaced persons camp in Bavaria) and Paris, came to London in November 1946. I went down from Manchester to visit them in London but did not stay. They wanted me to complete my schooling, so I returned to Manchester. In July 1947, having finished school, I moved to London and started work. The four of us lived in London until our emigration in 1948. My first job was with a company restoring rusty old chandeliers, presumably recovered from bombed houses. My assignment was to file off the rust. It was a dreadful job to be doing all day, but I discovered it was easier if I didn’t have to stand. Sitting was against foreman’s orders, and I was fired on the third Friday. I was too embarrassed to tell my parents, but I had plans.

Next Monday I went looking for work and luckily got a job as an electrician’s helper. Then I told my parents. I worked for the electrician until January 1948, when we left England. The job involved rewiring houses, hanging lamps, and repairing small appliances in the shop. I absolutely loved it. Once I accidentally put a foot through the ceiling when laying wires on the upper floor with the floorboards removed. My boss laughed it off and didn’t fire me.

My mother, never one to sit idle, found a job at the Palestine Club, cooking in the evenings. She had no work permit, but she needed the income. Eric had a legitimate job and continued to live in his apartment (or room?) within walking distance of my parents’ apartment. The latter, as I recall, was a single room with a gas heater that you had to feed shillings every so often.

I guess I was glad to see my parents again. I don’t remember my first sensation or expression when I met them after all those years. Maybe I disappointed them, or maybe I acted my part well enough. From the time I left London in November 1946 until July 1947, I was preoccupied with successfully winding up school. I think that basically I didn’t know what to say to my parents about their experience, so I confined myself to talking about my life. After all, if you don’t know how to empathize, what is the right thing to say to a sick, dying, or bereaved person when their plight is obvious?

My parents, on the other hand, talked freely and repeatedly about the camp, in great detail. They still talked about it decades later, and I’m sure that talking helped them heal. Eric was a better listener than I.

Problems eventually arose. I think I didn’t much want to be anyone’s child. The problem was threefold, being a teenager, having been so long separated, and having been raised much more orthodox than my parents ever were. Years later I came to realize their handicap, that they had missed the experience of the year-by-year transition of their children from childhood to adulthood. Eric remained more dependent and my parents found him easier to deal with.

Orthodox Jewish observance is compulsive and unforgiving. Eric had vowed to God that he would follow all the commandments if God would spare his parents. (He later broke his vow, but we never talked about that.) I hadn’t promised anybody anything; I was just orthodox — maybe because being orthodox meant knowing the do’s and don’t’s; and I was good at that. Since we weren’t allowed to turn lights on or off, go shopping, carry things outside the home, and many more necessary things on the Sabbath, we actually put our parents in the position of doing them. It irritated them but they complied because we gave them no choice. And for all the bad feelings we caused we weren’t even keeping our own souls clean, because asking another Jew to do forbidden things is as bad as doing them yourself. The religious problem really got to them years later, when I gave it all up on starting medical school, and it gave them powerful ammunition for opposing my marriage to a woman from a gentile home.

My parents’ aim from the beginning was to go to the U.S. They had only a limited period of legal stay in Britain and no permission to work.

None of us had regrets about leaving Britain. In retrospect, being bounced from one home to another (I can count at least ten in the 8 ½ years I was there) can’t be called a happy time, yet I have warm feelings for the country and enjoy going back to visit.

At the 50-Year Reunion of Kindertransport in 1989 I learned how some refugee children had been exploited and abused by their foster parents. Our experience was quite different. We were well cared for and educated.

Our crossing was on the De Grasse, a fairly small liner (about 20,000 tons), in January, a month of rough seas in the Atlantic. I was violently seasick the first day. A steward told me I had to get out into fresh air. That cured me, and I enjoyed the rest of the 10-day trip. Unfortunately we fell into the habit of leaving our shoes outside the cabin at night, to find them polished next morning. And we had so little money we didn’t tip.

IN THE UNITED STATES

For a short while we lived in a tiny midtown apartment with an icebox instead of a refrigerator. We then moved to Washington Heights (the nonaffluent section, east of Broadway). To get the apartment we had to bribe the landlord with $250 (almost 2 months’ salary at my first job). The landlord, named Singer, wore a stiff hat (which made him look rich) and was dubbed a thief by my mother. Uncle Max lent us the $250, which we later paid back.

In the early 1950s we moved to a nice 5-room apartment, 3rd floor walkup, in the Bronx, with views of Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds. (I’d become a bit of a baseball fan by then, and the Giants of that era were pretty good.) I left in 1957 to take my internship at Duke Hospital, and they moved again in 1962 to Flushing.

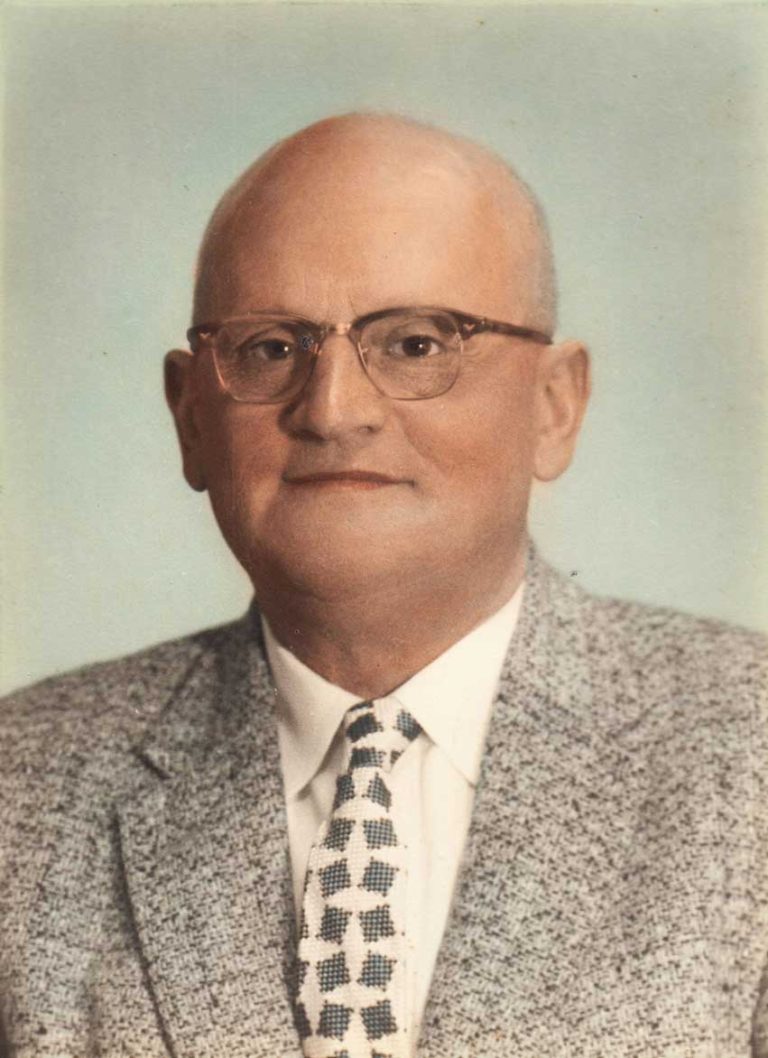

Max Heineman

My father Max fought in WWI and sustained a brachial plexus injury, which paralyzed his right hand (“claw hand”). He had to teach himself to write with the left hand and had to be helped in many ways. Still, he worked in Krefeld, Theresienstadt, and New York. What effect his lack of self-sufficiency had on his role in the family is speculative. It must have played into his relationship with my mother, who took the initiative in most things. Sadly he also had a naïve idea of biological inheritance. My mother told us he was afraid his children might be born with a paralyzed hand.

In Krefeld, he ran a small business in confectionery supplies. In New York, he worked as an all-around helper in a Wall Street investment house.

Max died of cancer on December 17, 1967, three days before his 76th birthday. This photo may have been taken at a hospital or convalescent home. Eric was always a devoted son, both during the wartime separation and throughout the ensuing decades until Lisette’s death of heart failure in 1982. Eric died of cancer in 1985.

Lisette Kaufmann Heineman

Four of my mother’s siblings, Alfred, Max, Sofie, and Erich, emigrated with their families between 1936 and 1938. I’m not clear why her sister Karola and my parents didn’t. My grandmother was said to be afraid of sailing, but my mother claimed that Max could have talked her into going to Cuba if he’d tried. Maybe so, but my mother wasn’t always objective where Max was concerned.

My mother enjoyed talking about her youth, growing up in the house of an apparently successful butcher. She used to hitch horse to cart before dawn to deliver meat. Her father (my Opa Isaak) was strict — to me her description was of a tyrant — yet she thought she was his favorite. She had an affinity for their animals: The dog (Lux) obeyed her command, as did the horse (name?), which she claimed to have led into their living room once.

She also told of dressing her youngest brother Erich’s festering leg wound (from WWI), and had ambitions (and, in my opinion, the ability) to study medicine.

This 1948 photo shows Max and Lisette, who had recently arrived in New York, with two of Lisette’s siblings and spouses. L-R Alfred, Lisette, Max, Sorma (Alfred’s wife), Bernhard and Sofie Lehmann. Alfred arrived in New York during the war from England. The Lehmanns left Germany in 1938 and settled in Cincinnati.

On one of my visits Uncle Erich slaughtered a lamb. It was a gruesome sight but the meat was delicious.

I don’t have a mental image of an actual butcher store, but it’s likely that Uncle Erich, who took over the butchery after my grandfather’s death, also sold meat directly.

Their place was close to the river Wied, a tributary of the Rhine, and was subject to flooding in the spring.

My mother went to school in Neuwied, with the single teacher (Ransenberg) living upstairs. The legend is that if he came down smoking a cigar he was in a good mood and the children would have a good day; if he wasn’t smoking he’d had a fight with his wife and would take it out on the children.

None of the six Kaufmann children had a secondary education — except Max, who evidently studied accounting. He eventually married Herta Frohwein, the daughter of a rich and reputedly corrupt man, and lived in Cologne. They had no children. Max and Herta emigrated to England before the war and on to the USA during the war. He settled in Washington Heights, NYC, where the German Jewish immigrants congregated (sometimes referred to as “Das vierte Reich” by its detractors). As a public accountant he cornered the market on German Jews and became wealthy doing their books and taxes. He was also very frugal and, according to Lisette, in old age (Herta having died before him) chose a nursing home in Jerusalem because it was cheaper than what he could get in NYC.

Antipathy between my mother and her brother Max was lifelong, fed by envy and Max’s overbearing personality. Still some sense of family remained. To enable us to immigrate to the USA he wrote an affidavit of support. We didn’t have to collect on it, because all three of us men quickly found work, my mother choosing to keep house for us. Decades later, during the couple of weeks between vacating his Washington Heights apartment and leaving for Israel, my mother invited her brother to stay in her Flushing apartment, which he did. When I later went to Israel on a seminar trip, she commanded me to pay him a visit; I obeyed.

He repaid his sister’s charity. In his will he excluded her and her children from any part of his abundant inheritance. To make sure this omission was not misconstrued as an oversight, he stated his intention explicitly.

Aunt Sofie and Uncle Bernhard settled in Cincinnati. I don’t know the reason for this choice. Their only child, Günter, served in the US Army in WWII. He married Eva and had children. I’ve never met them. One of them, Vivian, wrote a nice, loving card to her grandmother, Sofie, on her 90th birthday. My brother Eric used this to illustrate what a cad I was, since neither I nor my children expressed similar adoration for my mother. Günter committed suicide; I was never told any details.

Sofie was given to unpredictable behavior. On a visit to NYC, she got up in the subway and loudly sang a tune popular at the time, “Open the door, Richard!” Upon my mother’s death, it fell to me to call her. How Sofie took the news of her sister’s death I don’t remember. What I do remember is that she immediately lit into me about what an awful son I had been, including marrying a shiksa, about whom she knew nothing other than what she had been told by my mother and brother. The gist isn’t hard to guess.

Uncle Erich emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, with his wife Käthe and daughter Inge. In the late 1990s I spent a day with Inge in Sydney on a layover to visit our daughter Sue in Wellington, New Zealand. Inge came up from Melbourne just for this occasion. We exchanged a few letters after that but the correspondence fizzled out.