It was Lisa’s idea to visit the places of my childhood with me. Historians love site visits, and I, knowing that she’s intrigued by her international ancestry, jumped at her invitation. Her parents had met by chance continents away from either one’s birthplace, and their marriage blended different ethnic, social, and religious legacies. Lisa was born to diversity, first offspring of that “mismatch.” There’s plenty on both sides to occupy her, and in due course she’ll write a book. It’s a lucky parent indeed who can look forward to such a gift!

She’s already been to my birthplace in Germany. Sometime we’ll go back there together. But that’s for another day. Here we revisit my English Period.

To help with her 8-month-old baby, she recruited her 15-year-old niece. The four of us set out separately on June 24, 2011: Lisa and Julian from Cedar Rapids, IA; Rachel from New York City; and I from Newark. Aided by Lady Luck (and some planning), our three planes arrived in Manchester within two hours of each other. Here our ten-day pilgrimage began and ended.

Seventy-two years earlier I was an eight-year-old Kind enrolled in a Kindertransport, one of 10,000 children to whom Great Britain opened its doors after Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938. World War II would begin less than three months after my escape from Germany. My closest friends’ parents did not have the foresight or courage that mine did to send their children into the unknown. I never saw those friends or their parents again.

My war years began in Kent and ended, nine relocations later, in Manchester. In 2011 we followed a similar path. A two-day drive brought us to Cliftonville, near Margate. On a clear day you can see the French coast from there, and I remember early in 1940 watching a ship, probably having struck a mine, sink in the English Channel. My first home (not counting quarantine when scarlet fever was discovered), until our evacuation to the Midlands after Dunkirk, was Rowden Hall School, in the former summer residence of the margarine magnate Jacob Van den Bergh. It stood then at 13, Third Avenue. Now even its location eluded us; the block was a monotony of flats. Nothing was left to anchor my memories of homesickness, a sadistic housemother, horrid margarine, lumpy porridge, an outbreak of mumps, soccer games, and my first days in an English school. So we walked down to the beach, where in the gathering darkness we stood at water’s edge and dipped a finger (and Julian’s foot) in the Channel. It wasn’t what we’d come for, but it was something to remember Cliftonville by.

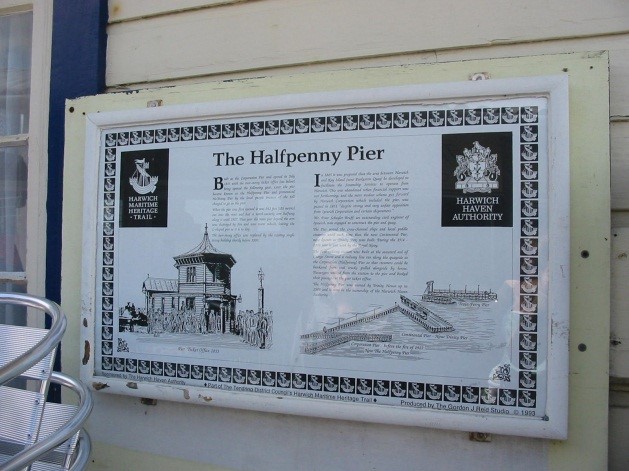

Shrugging off that inauspicious start, we set out for Harwich, Essex, now a busy cargo port but historically the entry point for thousands of refugee children, of whom my brother and I were two. On June 7, 1939, I reached Harwich by overnight ferry from Hoek van Holland; on June 29, 2011, via a 20-minute motorboat trip across the harbor from Felixstowe, Suffolk, where we stayed with English friends who have also visited us in Lumberton. Sadly, the vending machine on the Halfpenny Pier where I made my first purchase in England is gone. But then, the ha’penny that bought a small bar of chocolate in 1939 disappeared long ago together with all the mind-boggling currency of that time — farthings, shillings, crowns, guineas, and more — replaced by today’s decimal system of pounds and pence. I recognized no landmarks besides the dock, but before our return to Felixstowe Lisa sniffed out the Harwich Society, whose shelves held records of the immigration. Archives had saved the day, as they would a week later in Manchester.

More optimistic now, we drove on to the White House, once a girls’ hostel, in Great Chesterford, Essex. My trips there as a teenager (the first, in 1944, involving five different trains) are as much part of my history as any place I actually lived. Unlike Rowden Hall, this venerable structure has defied the centuries and still looks welcoming. What was once a girls’ hostel is now two private residences. I could not resist telling Liz Gamble, our hostess, about those visits — even the tender detail of carrying 13-year-old Irene up the staircase to the second-floor balcony. Enriched by the romantic history of her home, Liz walked us through the large garden in the back where sixty-six years earlier two teens had pledged everlasting love. (Postwar emigration modified that commitment to a more sustainable friendship.)

And so to Staffordshire, 1940-1944: four years, four homes, two schools. The house at 55, The Crescent, Boney Hay, looked just like it had. I stood and reflected in the living room where we’d once congregated nightly with our foster family, behind blackout curtains, during the air raids. I don’t remember being afraid; we got used to the drone of the bombers and even fancied we could tell them from the British planes. But like lightning in the countless storms we’ve all experienced, the bombs all hit elsewhere; we heard the thunder, flinched, and waited. In the end, the entire Crescent was spared, including the Ring O’Bells pub on the corner, where we bought dog biscuits to chew on when cookies were unavailable.

And here, in Boney Hay, I found my sole living human link to those days, just a couple of blocks from where she was born. Iris, now in her 70s, was my foster sister, five years old when my brother and I moved in and began tormenting her. Iris remembered it all. But she also revealed that I used to walk her to school — a pitifully inadequate way to repay her parents’ kindness.

George Turner was a coal miner, maven of an industry that once thrived in the Midlands. He biked to work five and a half days a week and spoke little.

We soon learned more about coal mining. Visible from our B&B in Brownhills stands a 40-foot stainless-steel figure. This impressive statue, titled “The Brownhills Miner” (2006), might as well serve as a memorial to the entire industry, brought to its knees by intractable labor strife. England now imports coal from Poland.

George Turner, dead of lung cancer, had been posthumously outsourced.

We continued to Walsall and Queen Mary’s Grammar School, which to this date I regard as the peak of my educational experience. Here the teachers wore robes, all students took Latin and French (Greek optional), and rugby was the sport. But it was too good to last. Another forced relocation cut short my stay after only two years. By then my home at 2, Walsall Wood Road, in the nearby village of Aldridge, had reached — if not passed — the limits of habitability. It’s gone now, but I immediately recognized the former pear orchard across the street. Most particularly the brick wall, which we used to climb to go “scrumping,” i.e. stealing, pears until we were chased off by the owner.

Curious about its interim history, we followed a chain of directions leading us to a woman in her nineties known to her neighbors as Pixie, an amazingly well-preserved descendant of our nemesis of yore.

She spoke with us of the 1940s and her service in The Royal Navy, and showed us pictures of an Aldridge I never knew. The orchard, sadly, did not age as gracefully as Pixie. Houses have replaced part of it, and scrumping no longer pays. If only today’s youthful denizens of Walsall Wood Road knew what they missed!

Mary Tudor founded the school that bears her name in 1554. When I first saw the buildings in 1942, I assumed they were original, and I pictured the Queen herself dedicating the school right there. In fact, they’d been rebuilt just 93 years before my arrival!

Those buildings once surrounded a large playground, scene of many a pick-up ballgame and many a pick-up fist-fight (never a weapon), and used only by the boys. Girls attended Queen Mary’s High School, on the other side of a wall. In 1961 a brand new school was built a couple of miles away. Predictably, being new, it was for the boys. The girls inherited the old campus, and the playground, no longer needed for rough games or fighting, became a parking lot. Still, the students who took us around — seniors, exempt from the school uniform and allowed makeup — represented a proud group who equalled the boys on national exams.

If my long-treasured memory of QMGS was ill served by these changes — and it was — worse awaited me in Manchester. North Manchester High School for Boys lacked the stature of Queen Mary’s, but it did have a small greenhouse. In this gathering place we socialized, generated nitrogen dioxide (a malodorous, toxic brown gas) for fun, and learned some botany. The assembly hall sported a plaque with my name as a university scholar-ship winner. But all that was before a hurricane named Progress leveled the school. Early in July 2011 a duo of amateur archaeologists recovered brick fragments from the weed-covered plot where it had stood. After that I had no enthusiasm for visiting the box-like new school building down the road.

Gone too were the four homes in which I’d lived in succession during those years. One had had no electric lights; we read by genuine gaslight — a lot of bother and no romance. Their disappearance was no surprise.

And just when it seemed that the past had vanished entirely, archives again came to the rescue. With characteristic resource, Lisa dug up records of me and kids I’d known, kept by the Manchester Jewish Refugees Committee. I expect she’ll return to continue digging.

With that our pilgrimage was over. Next morning we left as we’d come, for three different destinations.

As I traveled this road of rediscovery, a hint of nostalgia was never far behind. England holds a powerful attraction for me, which may seem remarkable given that it’s where I, a vulnerable eight-year-old, experienced indefinite separation from my parents with no caring surrogates to take their place, homesickness, uprooting over and over, and wartime privation. Yet I still have a warm spot for the country and for the memories of those years. Maybe it’s the power of that glorious first crush of youth; maybe it’s Queen Mary’s; or the Manchester City football team; or the school trip to the dark depths of a working coal mine; or my varied recreational life. Were I to chronicle that period, I would not bemoan the travails of a lonely refugee child; I would write about the joys of growing up as an English schoolboy.

After surviving three years in the Terezin (Theresienstadt) concentration camp, my parents joined my brother and me in England in 1946.

Lisa is a professor of history at the University of Iowa.